What if…

WE END MATERIAL SCARCITY?

It’s surprisingly hard to imagine a world without scarcity. When we think about the end of material needs, it’s usually our own, says John Quiggin, an economist at the University of Queensland in Brisbane,

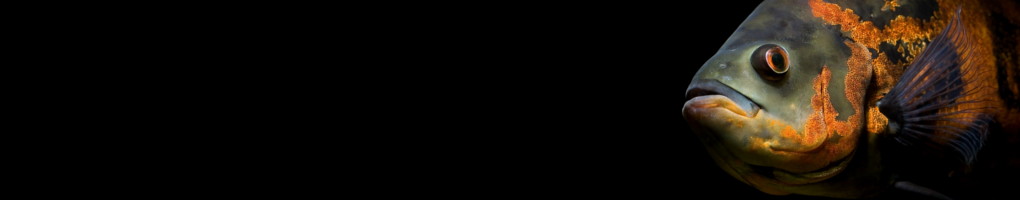

Australia. But what about everyone’s needs? “Scarcity is the basis of our fundamental economic system,” he says. This is the capitalist paradigm whose principles are, to most of us, as non-negotiable as the laws of physics. How would the economy work if everything was free? Who would make things if no one got paid? Isn’t this just communism? Trying to envision a world not organised around the market is a bit like a fish thinking about what’s outside the water.

fish thinking about what’s outside the water.Jeremy Rifkin did it in his 2014 manifesto The Zero Marginal Cost Society. Capitalism, he contends, is almost done eating itself. “It’s the ultimate triumph of the market” – a final transition to a society in which automation has brought the cost of producing each additional unit of anything near to zero, and products are essentially free.

For a taster of how this looks, consider the music and publishing industries. The internet has made the production and distribution of content incredibly cheap. Though painful for some, Rifkin sees this

trend as the harbinger of a new paradigm that will spread to all other industries. A critical enabler will be fabrication devices that can make almost anything on demand: think of today’s 3D printers but immensely more sophisticated, like a modern computer versus a 1960s electronic calculator.

Within 60 years, these devices might have evolved into machines called molecular assemblers. The term was coined in 1977 by

Eric Drexler. He imagined a nano-fabrication device capable of manipulating individual molecules with sufficient speed and

precision to produce any substance you desire. Press a button, wait a while, and out come food, medicine, clothing, bicycle parts or anything at all, materialised with minimum capital or labour.

We can’t know what such a world would look like – but the outlines are becoming visible. Rifkin thinks fabricators will be the engines of a sharing economy. The concept of ownership will give way to access (think Spotify and Uber for everything); purchases will give way to printing whatever you need. Within 20 years, he says, “I don’t think

capitalism is going to be the exclusive arbiter of economic life. It will share the stage with its child.”

Within 60 years, capitalism might have left the building completely. In its place will be a society in which all our basic needs are met. Rifkin calls his new economic vision “the commons”, but it goes beyond the economy – it will be the new “water” we swim in.

You will have a job, but it won’t be for money. The company you work for will be a non-profit. Your “wealth” will be measured in social capital: your reputation as a cooperative member of the species. So

when you contribute to open-source code that makes a better widget, you’ll enjoy a “payment” in the form of an improved reputation. Apps that track your contribution to the commons – whether by your input at work, your frugal use of energy, or other measures of reputation – will let you cash in your karma points for luxuries, say, an antique chair that was conspicuously not built by a fabricator. Even in the commons, we’ll still be human. (Sally Adee)

p. 40 | NewScientist | 19 November 2016